Same Kind of Different As Me

THROWBACK THURSDAY - First published 11/19/2007

Created 11/19/2007

One was a modern-day slave and then the toughest con in Angola Prison. The other was a yuppie art dealer. A violent miracle and a tragedy brought them together in eternity.

By Bob Gersztyn

Photography by Kimberley Smith

Ron Hall and Denver Moore are as unlikely a pair of friends as you'll probably find anywhere.

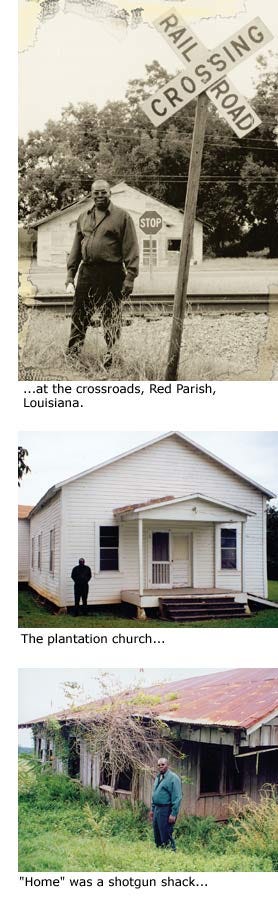

Denver Moore grew up on a plantation in Red Parish, Louisiana, where he lived in a shotgun shack as a modern-day slave until he escaped to freedom at the age of thirty. Freedom brought the uneducated and financially destitute Denver the gift of homelessness, which eventually led to ten years in the legendary Angola Prison for armed robbery. After his release, he ended up back on the streets, as a hardened criminal who frequented the Ft. Worth, Texas, Union Gospel Mission.

Ron Hall grew up in Haltom City, outside Fort Worth, Texas. He attended college, earned an MBA, got married, had kids, became an international art dealer selling million-dollar Picassos, and volunteered to help serve dinner once a week at Ft. Worth's Union Gospel Mission, with his wife Deborah.

The reason why Ron and Deborah were volunteers at the mission was because of a dream that she once had. In it, she saw the fulfillment of Ecclesiastes 9:15, which talks about a poor wise man who changes the city. The first night they were serving dinner, a crazy man assaulted twenty people and threatened to kill anyone who tried to stop him. That man was Denver Moore, and when Deborah told Ron that he was the man in her dream, his heart sank.

After a series of gritty encounters and fervent prayers, multiple miracles occurred, and over a cup of coffee in Starbucks, a friendship was forged between Ron and Denver. That story, the woman who inspired it, and its ramifications are documented in 2006's emotionally charged book, Same Kind of Different As Me [1], published by W. Publishing Group—a division of Thomas Nelson Publishers.

And that's only HALF the story ...

WITTENBURG DOOR: How do you change lives and heal hearts?

RON HALL: First of all, the way I've seen it with Denver, and seen it with the others, you have to get to know the person, and know their heart. You can't judge a person by looking at the outside and figuring out whether you're going to be able to help them, or what the condition of their heart is. I believe the only way that you can do it is by spending time with that person and not judging them. Just serving them, getting to know them and just loving them. Government programs and faith-based agencies kept Denver alive on the streets for probably thirty years, but it was the first time that somebody loved him, when Deborah loved him, and that made him want to change his life.

[2]

DOOR: When Deborah saw Denver in a dream and related it to Ecclesiastes 9:15, what did you think about that?

HALL: Deborah was always one of the most intelligent people I'd ever known. She was also the most believable person. She didn't exaggerate. She didn't lie. Everything about her life was about the truth. She sought God and she spent a lot of time with God, in prayer and seeking what He wanted in her life. So I didn't question anything that Deborah said. I was hopeful that she wasn't going to ask me to go look for him with her, but I sure didn't question that she had seen the vision.

DOOR: What did you think when Deborah suggested that the two of you volunteer to help out at Union Gospel Mission?

HALL: I was always one that was more interested in writing checks than getting my hands dirty. I really didn't care. I was more interested in spending time at our ranch than I was volunteering to feed a bunch of homeless people. I really didn't have that kind of heart, but Deborah had that heart for many years. She had served homeless people and other indigent people for years in various forms. She invited me to do those kinds of things before, but mostly I was just the person who wrote the checks to support those kinds of ministries.

After she forgave me for an affair and never brought it up again, I was determined that for the rest of our lives together, as a married couple, I would do basically anything that she asked me to do. So even though I didn't want to do that, I wanted to do that for her, because she wanted me to. I was willing to please her, and not really to serve God or homeless people or anything else.

DOOR: Denver, how did God speak to you when you were living on the streets? Did you consider yourself to be a Christian back then?

DENVER MOORE: Yes, I considered myself to being a Christian. I couldn't be nothing else but a Christian. I considered myself as being a Christian, because I have always been. That's been drilled in me from a child. So just because I was in the streets didn't make me stop believing in God and His mercy because that's all I had to lean on—the mercy of God. This is how I'm sitting here today, speaking with you, because of the mercy of God. He took care of me for the many years on the streets with nothing—no house, no car, no land, and no money. That's about it there.

HALL: I can tell you that Denver had a saying, years ago, when we first met. He said, "You know, it's really something when you can thank God for nothing, 'cause all my life I've had nothing. I can still thank God that I had nothing." Of course, the first time I saw him, he'd just beaten up about 20 people and threatened to kill everybody in the room. He was very scary to me, but that was a facade that he had to maintain. The reason he's still alive today is because he lived life by intimidating and by being the lion of the jungle.

But the truth of the matter is, he also ran a protection racket, for all the homeless people that couldn't take care of themselves, for the mentally ill people on the streets that the punks and thugs would go beat up and take what little money or possessions they had. He was the number one enforcer in the inner city and the hobo jungle. Anybody that was too weak to take care of themselves, Denver would protect them.

DOOR: Tell us about "Mr. Ballentine."

HALL: The other homeless people used to beat up Mr. Ballentine. When Denver wasn't around, they'd beat him down because Mr. Ballentine would just look right straight at a black man and call him "nigger." Then they'd just do a number on him, beat him near to death. Then as soon they'd get through beating him, he'd say, "You might have beaten me up, but you're still a nigger." So they'd beat him again. When Denver would find that out, he'd go take care of business and then they'd leave Mr. Ballentine alone.

He showed the love of Christ in a way that nobody else can really say. Nobody would have thought he was going around showing the love of Christ on the streets, but what he was doing was actually showing love to the people who were totally unlovable by protecting them. Many of them would be dead today, had he not. As Denver said, taking care of business, by beating down the man that was beating up on the mentally ill people.

DOOR: How did you first come to know about Jesus, Denver?

MOORE: I think that wisdom sometimes out-whips education, because with education, you are talking to a program. I started seeking wisdom, knowledge and understanding. People read the Bible with me. My uncle kept reading the Bible to me for many years. In prison they read the Bible to me for many years and that's how I obtained the knowledge and the wisdom that I have now. Wisdom compasses all understanding. Thank you.

DOOR: Where else did you gain wisdom?

MOORE: I learned about most of that as being homeless and meeting homeless people. Some of them was veterans from different wars and what have you and they started teaching me a little about American history. I learned lots of it in Angola State Institution for the Disobedient.

DOOR: You escaped from the plantation in Red Parish by hopping a train that eventually ended up in Fort Worth. That's when you eventually ended up on the streets. How do you compare life on the streets to life on the plantation?

MOORE: Life on the plantation is better. The difference is with life on the streets, we have to understand that those people mostly have a mental defect somewhere. This is the reason why they become homeless and they move from one spot to another one. I become homeless because I had a defect because I wasn't getting paid right and I didn't have no funds at all, so that was a defect. So by me going homeless, being broke was broke either way it goes, so I might as well be homeless, and didn't have to work, than to be broke after working all them years. Thank you.

DOOR: And from there, you ended up in Angola. Other than regularly fending off rapists and murderers, how did your 10 years in prison compare to your life on the plantation and life on the streets?

MOORE: Life on the plantation gave me the ability to work in prison, because that's all this was at that time—plantation work. That's where I started working at in prison: cutting sugar cane, and picking okra and beans, peas and all this different kinds of farm work. When you first go to prison, the first thing you have to do is express yourself as being a man, to get any respect at all, back then. Because someone is going to try you when you first get there. When they find that you are weak, and you can't stand up for yourself, then you end up being what they want you to be. I'll put it that way, and that way I won't offend anybody. So it's enough to let you know I was a man when I went there, and I proved myself as a man when I was in there, and I was a man when I got out. I just can't tell you too much more about that than that.

DOOR: How did you feel about the lady in Fort Worth who gave you a sandwich every day when you were sleeping in a doorway?

MOORE: I felt real good to know that she would come there every morning. She started treating me just like I was one of her children. I really respected that, and then she helped me to get up. Because when the man was coming that runs the place, she'd come out and tell me to pack up my goods and move around a little bit. She was a very beautiful woman, a wonderful person. No sir, I don't know her name. I never asked, but she did that for many and many a month.

DOOR: Why didn't you ever ask anyone their name, prior to asking Ron his?

MOORE: Being homeless, you don't need to know nobody's name. You don't ask people their name because you don't never know why he is homeless. And they're not going to tell you his right name in the first place. So when I become homeless, no one really knew my name. You know? And whichever name they pick out and call me, then that's fine, that's what I answer to. This is what all homeless people do. They don't go around knowing each other and that.

DOOR: I understand that in some of the shelters run by religious groups you have to listen to a sermon before they'll feed you.

MOORE: I feel that one of the most positive things, and Christian duties, is to try and help those who has got lost in life. They use that when you go to the mission to eat. It was a primary thing in the past that when you go to the table to eat as a child, someone would always say a prayer, and this is how the mission come to that, because it's serving God's purpose, helping the helpless. And when it's serving God's purpose to help the helpless, then the helpless need to listen at what they said, it's because (they're) trying to bring your mind back to reality. So the gospel being preached in the missions around America needs to be preached. If Christ was based in the life of the homeless who are sitting out there, then they would not automatically complain. People often complain about the bad things that other people do, but they never said nothing about the good things that they do. You're getting a meal free. You weren't on the plantation. You weren't working in the penitentiary. A free meal? Oh, come on now, let's be real.

HALL: The truth of the matter is when Deborah and I were serving there, there were still people who didn't want to hear a Gospel message to get a free meal. Mr. Ballentine was one of them. He would rather starve to death, he said, than hear a Gospel message. I don't think he ever went to chapel. I never saw him there. There were other people out on the streets that would actually give them the sandwich, so those people didn't have to come in and hear a message.

DOOR: Ron, you said that Deborah and her best friend Mary Ellen Davenport turned foot-washing into an art on Beauty Shop Night at the mission. Talk about that.

HALL: They did that with the women. The homeless women had a separate building at the mission that we didn't go into. They would go in and clean up those women. It didn't surprise me. Nothing that Deborah did surprised me. She genuinely had a heart to serve others and to see a change in their lives. She knew that in order to help somebody out of a ditch, you got to get in there with them and let them climb up on your shoulders to get out. So she would get down as low as you could get, and be a part of their lives, on that level. Washing their feet was something she felt like she had seen in the Bible. That was just the way she really wanted to minister to these ladies.

DOOR: When did you first suspect that your interest in befriending Denver might be less than honorable?

HALL: I began to believe that there had to be some reason why he didn't want to be my friend. I couldn't imagine why—here I am a wealthy man wanting to be a friend with somebody who had nothing and I kept thinking of all the things that I could do for him. I never really considered the other side of the equation, what he might actually do for me or my family. So it was just a self-centered kind of request.

After a few months of chasing him around and thinking, "This guy's a nut case ... doesn't want me for a friend so there's something wrong with him," all of a sudden it just dawned on me that maybe it is something about me. Why would this guy want to be my friend? Maybe my motives really aren't pure in beginning this friendship. I don't really want to be his friend, I've just been looking for some kind of a trophy so people will think that I'm a good guy.

DOOR: Finally, you write, Denver asked if he could ask you a personal question ...

HALL: He had stared into my eyes with eyes like laser guns, many, many times, but that was the first time we ever actually sat down and had that conversation. I really didn't know what he wanted. For him to ask me a personal question, I thought he wanted to know first of all, "Where do you live?" and "How much money do you have?" At the mission they warned us when we began to be volunteers, three things—Don't tell them your last name. Don't tell them where you live. And don't give them money. When he just wanted to know my name, I thought, "Why in the world? I mean that doesn't make any sense, if somebody thinks that's a personal question."

DOOR: Denver, explain your term "catch and release friendship."

MOORE: Catch and release friendship is when I was looking at TV and saw bass fishermen catch them big bass, then they'd throw them back off into the water. So that's the same kind of difference as people that's accepting people who are homeless—because sometime when they realize that they don't really have an impact on them, they put them back where they got them from, just like they throw the fish in the water. They throw the brother back right where he came from. That means that he gets a chance to swim in muddy water again.

If you get something off the streets, you know you got it off the streets. But when you get something off the streets, you don't never know if you shine it up it might be gold and become a precious jewel in your life. That's all of us.

HALL: The truth of the matter is, friendship to Denver meant a whole lot more than to me. Friendship to me is acquaintance. I say I have friends all over the world, but they're more of acquaintances. Friendship to Denver, in the truest sense of the word, and he will tell you, is somebody that would give his life for his friend. That's why he didn't really want any friends. He didn't really know anybody out there he was willing to give his life for. He didn't really care whether he had any friends or not. When I came along and asked him if he would be my friend, that meant that he would actually have to give his life for me, if that came up. That's never what I would have considered. I just wanted to be his partner and kind of hang with him, and not have him run from me.

I was still scared to death of him, even on the way to that catch and release meeting in Starbucks. He looked at me and he had such anger, and the way he talked to me and looked at me, I was still afraid he might actually kill me. Just snap and kill me, because he was a scary-looking and scary-acting person. But after that catch and release meeting, the fear that I had for him just melted away, and then we became friends. That was eight years ago. We've been lifelong friends ever since.

DOOR: Ron, you and Deborah used to greet each other in the morning with, "We woke up!"

HALL: That all started when she was down on the lot with Sister Betty...

DOOR: This was the elderly woman who, after her husband died, sold all of her possessions and moved into the Union Gospel Mission in Fort Worth to help the homeless. She was Deborah's inspiration.

HALL: Right. There was this man, who was the hardest core of the homeless people. He lived in a cardboard box, underneath the railroad trestle, and had the long, long beard, and probably bathed maybe once a month or less, and he smelled bad. He looked to be 80 or 90 years old, but I don't know how old he was. He might have been my age. One day he was just smiling at Deborah as she was feeding him. She asked, "Why are you so happy?" And he said, "Because I woke up." That's just the reason enough to be happy. All of a sudden, it dawned on us that we had so many things in life. We never stopped in the morning, when we woke up, just to thank God that we actually woke up.

DOOR: But then on April 1, 1999, that little saying took on a whole new, deeper, darker dimension...

HALL: It was about that time that we found out that Deborah had cancer. We said, "You know, it's a profound statement when in the morning you wake up to thank God that you're still alive." We did that every morning until the day she died, except the last three weeks, when she was non-verbal. I still said it with her first thing, even when she was in a coma. I would look up and say, "Debbie, we woke up, we're still alive, we're still fighting." I even do that today, when I wake up in the morning, I still think to myself, "Well, I woke up." And that's reason enough to be happy.

DOOR: Deborah died in November 2000 of liver cancer. How did you eventually forgive God after Deborah's death?

HALL: It took a while because I realized that it wasn't doing me any good to just continue to be angry at God. I still can tell Him today that I'm disappointed at the outcome, but I can see a lot of fruit. I can see that Deborah's vision, her dream, all those kinds of things that have come to pass that would not have happened in her lifetime, things that happened as a result of her death. So I can embrace that, even though I can't deny the fact that I would rather her be with me today and enjoying this. I can't deny that I would rather be serving at a mission that wasn't named after her, for her death, but letting her serve there in life, doing the work that she was called to and loved to do. I finally realized that it was not doing me any good, I was just dragging myself down to be angry with God, because He is God.

DOOR: Denver, how did you know that Satan was going to attack Miss Debbie?

MOORE: That's because the Spirit touched me and said something from a subconscious state to a conscious state. I have an understanding to know that when people are precious to God, they become important to Satan. And he's here to steal, to rob and to kill. The thing about it is that Miss Debbie left something when she left ... that I should pick up the torch and keep the ball to rolling. So that the things that she left would always create new life in other people's lives through love.

You know, sometimes I believe that it is time for us to start serving instead of judging. If we serve without judging, then God bless us for serving without judging. Why, when, where, who? What difference does it really make? Let the Christ in you be the hope of glory.

DOOR: Denver, after burying Miss Debbie, you said, "That's the good thing about God. Since He can see right through your heart anyway, you can go on and tell Him what you really think." Is it okay to cuss God out?

MOORE: No sir. Not in my realm. It doesn't make sense to cuss at God. We must have a positive understanding. God gave us the spark of life and that spark that brought us into the world, and we just can't never try to put out the spark that brought us into the world. We are what we believe in, you know? Whether we believe whether there is a God, or whichever His name is, doesn't even make no difference. Just serve instead of judge. So we have to understand that the bad makes it bad for the good, and the good got to suffer for the bad. If the bad makes it bad for the good, and the good got to suffer for the bad, that brings us to a point in the Scripture where it says after six days God has finished all things and everything He had done He looked over, and He looked back, and He said, "This is all good, and this is what's going to make the world a better place today." This is when we can look out for those who can't look out for themselves, to help those who can't help themselves. That's when God can look down on us and say, "It's all good."

[Editor's note: A year after she died, Ron and Denver helped raise $500,000 to build The Deborah Hall Memorial Chapel at the United Gospel Mission. Both men are still active at the mission. Ron and Denver now share a home on a ranch outside Fort Worth.]