Sacred Clowns and Surgical Satire

Humor is hard.

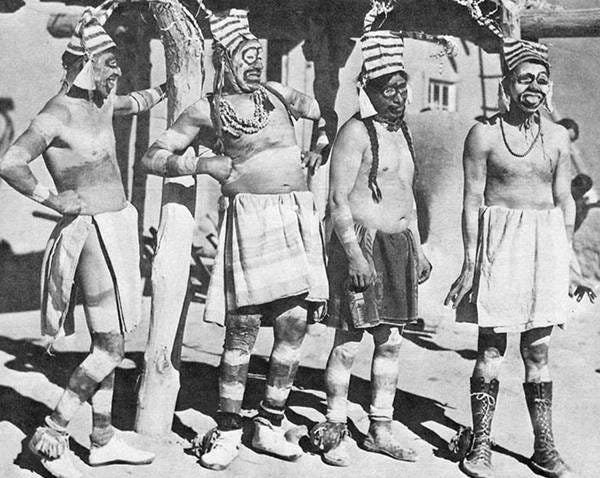

Photo: Tewa Clown Society members, San Juan Pueblo, N.M., 1935

You may not realize this, folks, but humor is hard. (Just look at the exhausted stand-up comics in the photo above).

Seriously, I really struggled with a piece of satire I was writing the other day.

Long story, but I was caught between wanting to mock a particular aspect of human pride, while not wanting to completely shame those who were my targets, or demean others that I was using as counter examples.

I had to stop and ask myself, Why do I want to do satire in the first place?

I’ve written about this before, in a rumination on the need for a jester in a medieval court, who acted as “a counterweight to the gravity of the king, a reminder to those in authority of the need for humility.”

But this time I ran across more fascinating examples from history and anthropology, and they involve shame.

Guilt and Shame

First, a clarification: Guilt is the inward, private feeling of regret we feel for our actions. Shame is our response to a public exposure of our sins.

The fear of public shame was found by Aristotle and Confucius to be essential for ethical behavior and social order. In primitive societies, the shame of breaking a taboo was so powerful it could even lead to "psychic death."

The biblical Job said the shame of his situation was so intense it was as if “my flesh is clothed with maggots.” Yow!

A modern “guilt” society like ours depends on a strongly developed inner sense of self and individuality. But we still carry around a sensitivity to public opinion—the threat of being cut off from our group, clan or tribe.

Even now, public shame can make us blush, and reduce us to silence, immobility or hiding.

In Native American societies, the role of the jester was played by a tribe’s tricksters and clowns. The following descriptions are paraphrased from the Wikipedia entries on these interesting individuals:

Upside Down and Backwards

The Sioux had the "heyóka"—a kind of sacred clown. The heyóka is a contrarian, jester, and satirist, who speaks, moves and reacts in an opposite fashion to the people around them. They provoke laughter in distressing situations of despair, and provoke fear and chaos when people feel complacent and overly secure, to keep them from taking themselves too seriously or believing they are more powerful than they are.

They use satire to question the specialists and carriers of sacred knowledge or those in positions of power and authority. They are the only ones who can ask “Why?” about sensitive topics.

By purposely violating norms and taboos, they help to define the accepted boundaries, rules, and societal guidelines for ethical and moral behavior.

The role of a heyóka came as a special calling, after he received “visions of the thunder beings.”

Heyóka have the power to heal emotional pain; such power comes from the experience of shame—they sing of shameful events in their lives. The heyóka functions both as a mirror and a teacher, using extreme behaviors to mirror others, and forcing them to examine their own doubts, fears, hatreds, and weaknesses.

By reading between the lines, the audience is able to think about things not usually thought about, or to look at things in a different way.

The Pueblo Clowns of the Kachina religion play a similar role. Anthropologists note that they were sometimes feared by the community as the source of public criticism and censure of non-standard behavior.

Standing the World on its Head

The Hopi (the westernmost group of Pueblo Indians) claim they emerged into the world in the beginning as clowns, and thus clowning symbolizes the sacredness of humanity. It reminds the people of the problems that are inherent in everyone. The clowns stand the world on its head in order to reveal its rules and their necessity to abate chaos. Clowning can be used to publicly shame potentially troublesome citizens into accepting community standards.

Some of their methods are totally outrageous. Often they employ depictions of sexual acts and lewd remarks, reminiscent of the Cynics in ancient Greece who adopted unconventional lifestyles and rejected traditional customs as a critique of society.

Here is a quote from the 1902 annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology describing sacred clowns among the Zuni:

Each clown endeavors to excel his fellows in buffoonery and in eating repulsive things, such as bits of old blanket or splinters of wood. They bite off the heads of living mice and chew them, tear dogs limb from limb, eat the intestines and fight over the liver like hungry wolves... The one who swallows the largest amount of filth with the greatest gusto is most commended by the fraternity and onlookers. A large bowl of urine is handed to a Koyemshi, who … after drinking a portion, pours the remainder over himself by turning the bowl over his head.

Now that's going the extra mile to make a point!

Despite its peculiarities, the trickster/clown role seems to meet a universal need in every society. Here's a report from India:

The priests of a Bhagavathi Amman temple in Kerala, India, perform an elaborate costumed dance portraying the battle between the goddess Kali and the demon Daruka. One of the main characters is one of Kali’s servants, a bizarre, comedic clown-like woman with bare breasts like red bananas (played by a man). The sacred clowns were shooting big jets of real fire using a primitive sort of flamethrower, very close to people who were not part of the show.

In Jewish tradition, no one person takes this kind of role, although the Old Testament prophets regularly mocked idolatry among the people. Rather it's a time of year. Purim becomes a venue for crazy antics, costumes, skits and parodies and making fun of the rabbi, the Talmud and Jewish liturgy itself, which is never done at other times.

Shame shows us that faith is not just an inner piety; it should be reflected in our actions. Our actions can shame us as well as produce the pang of inward guilt.

But jesters who go too far can be executed. And mockery taken too far can harm or kill.

Reintegration, not Ostracism

In “Is Shame Necessary?” author Jennifer Jacquet examines the dangers of shame, and its benefits. Shame is powerful but imprecise, meaning it must be deployed “shrewdly,” she says, with “scrupulous implementation.”

Another author, Cathy O’Neil in her new book “The Shame Machine,” reminds us that Frederick Douglas used shame to good effect against “the contaminating and degrading influence of Slavery.”

O’Neil refers to the Native American clowns and their mocking rituals, and notes, “The purpose of the ritual is reintegration, not ostracism: The people they mock remain members of the community.”

And this makes perfect sense. To be effective, mockery should be as delicate as surgery. There has to be a “humanitarian corridor,” an escape route left open for repentance. Otherwise shame can isolate and crush someone’s spirit, and even lead to suicide.

Of course, humorists should always punch above their weight, mocking the powerful rather than the weak. But even here, there should be limits. Do we want to expose something irrelevant, that might ruin someone's life, just to make a point or get a laugh?

To first not take himself seriously is the essential requirement of the satirist. Christians especially must remember to first see themselves as “fools for Christ” before pointing out others’ foolish behavior.

The bottom line? Satire—at least the kind we do at The Door—must be redemptive. Otherwise we're just being mean.

But to be clear, I am not going to strip off my shirt, paint stripes on my chest and simulate a sex act. At least not in public.